Link: https://grimes-gif.github.io/ML_Psychiatric/

Psychiatric classification

Machine learning project at Georgia Institute of Technology Collab: Saif Syed Ali, Ibraheem Abutair, Matthew Johnson, Micah Grimes

Introduction

The objective of this project is to use machine learning to gain insight onto potential predictors or biomarkers present in the brain of patients diagnosed with psychiatric disorders.

Ideally the inclusion criteria is as follows:

- Subject must have been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder by a medical professional

- Must be having a current psychiatric episodes OR has had an episode in the past 6 months.

We believe that machine learning is especially useful in this field because it allows for the standardization, comparison, and subsequent analysis of datasets that come from different metrics/studies. Succesful completion of this project would allow us to provide physicians and researchers with possible predictive measures for the development of psychiatric disorders.

Pictured above is a generic electrode map, with the top representing the front of the head. The electrodes are named after their respective brain region: for example, the “O1” and “O2” electrodes monitor brain activity in the occipital lobe. Likewise, the “FP1” and “FP2” electrodes monitor brain activity in the frontal cortex.

Methodology

Data types

Our first task was to go about trying to decide what measurements would be most useful to building a psychiatric classifier. Neurological imaging and EEG data came to mind as they are both non-invasive and carry minimal risk. However, in our search we found that securing MRI/fMRI images was extremely difficult with many studies being blocked behind a paywalls, not providing enough scope to be a psychiatric classifier, or providing a sparse amount of data points. Due to these limitations, we setteled for using EEG datasets, which is much less expensive to perform and use.

Dataset

The dataset we selected was an EEG dataset with 2 sets of labels from kaggle. While this data was much more plentiful than other sets we came across, it unfortunately had very little documentation, so data cleaning and analysis was a bit harder than usual.

Dimensionality and Description

- Rows = 945 patients

- Columns = 1149, for a total of 1148 recorded features (One column being an empty divider between the recordings)

- The first 114 columns were the frequencies of each sensor with respect to a particular frequency range, categorically known as brain waves

- 19 electrodes, 6 brain wave classes = 114 readings

- The 115th column is empty serving as the aformentioned divider

- The rest of the dataset from column 116 to 1149 were coherence measurments, which capture the ‘communication’ between regions by measuring the frequency in which the two regions share wave formations. This is more formally known as phase-amplitude coupling.

- The first set of labels consisted of strings that were the specific disorder each patient had. This set consisted of 12 unique values.

- The second set of labels consisted of the more general groupings of each disorder, called the main disorders. This set consisted of 8 unique values.

Note: In this analysis we only used ‘specific.disorder’ labels which consisted of 12 unique values, more analysis can be done to see if these values were too specific to be categorized by EEG.

Data cleaning, Feature extraction, Engineering, and Reduction

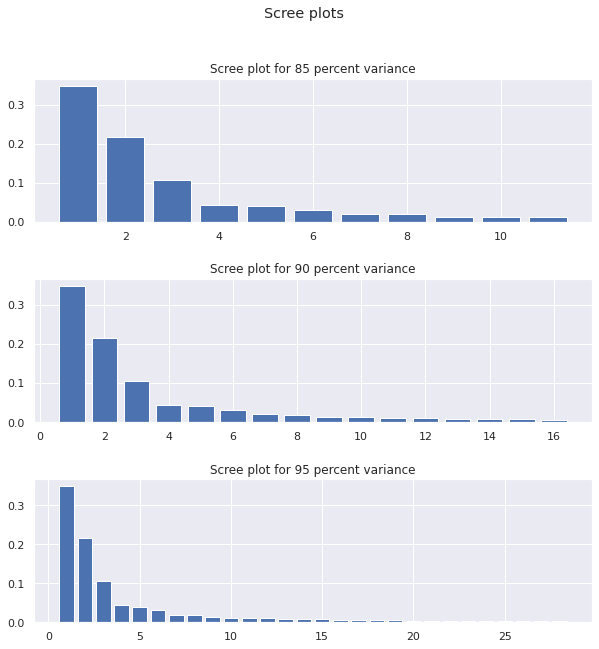

- Initially, PCA was run on the entire dataset in order to reduce dimensionality. This was a must, as the initial dataset contains over 1000 features. After running PCA, we found that aiming for even 70% recovered variance led to 40+ components, which still wasn’t ideal. Thus, we decided to divide the data into subsets using feature selection. See results for more information.

- After PCA analysis we decided to do feature extraction, columns 116 - 1000 were all coherence values between each electrode. Since we were not particularly interested in these values and more so the raw frequencies of each wave, we dropped these columns. This instantly made our dataset much easier to work with. Next, for the supervised learning portion, we focused on major depressive disorder (MDD), which allowed us to drop all rows pertaining to other disorders. Lastly, we focused on the frontal parietal lobe (FP1 and FP2 electrodes), as this a critical brain region involved with higher-order thinking. All of these feature selections allowed us to create a workable dataset, which we run several learning algorithms on.

Feature engineering involved normalizing the wave frequencies in order to yield more accurate/consistent models.

Data preprocessing consisted largely of isolating subdata sets and particular features to work with that would increase metrics for our models, this was because the main bulk of the work, transferring time series data to frequency domain had already been done by the authors of the dataset using FFT. Additional preprocessing done by the dataset authors included removing EOG (eye movement) artifacts from the frontal electrodes, allowing for a high confidence of signal to be neural in nature.

Machine Learning

For unsupervised learning (US), we used the many tools available to us that quantifiably measured how certain data is distributed in a given data space. We performed a kernel density estimation on selected features that we believed would have significance, as well as clustering analysis, both soft and hard, to find out if certain neural oscillatory behavior was distinguishable between values of the target labels.

For supervised learning, we used Support Vector Machines, Neural Networks (Perceptron), Decision Trees, and Regression (specifically, stochastic gradient descent). For the SVMs, LinearSVC, SVC w/ a Linear Kernel, SVC with an RBF Kernal, and SVC with polynomial kernel were attempted. The polynomial SVC yielded the best results. In depth explanation of these methods are covered in the results and discussion sections.

Results

Feature selection, engineering, and reduction

Results of Principal Component Analysis:

def compute_PCA(data, percent_Var):

pca = PCA(percent_Var)

pca.fit(data)

x_axis = np.arange(1,pca.n_components_ + 1)

return (x_axis, pca.explained_variance_ratio_, pca.fit_transform(data))

The large number of principle componenets required suggests that the variance over the entire dataset was scattered about and not that easy to grasp, motivating the creation of subdata sets to grab data points that were related to each other in order to have cleaner results.

Nonparametric methods

Due to the incredibly large number of features (1000+) in the dataset, it is important to conduct informed data analysis to perform targeted machine learning. This was accomplished by specifically examining the FP1 and FP2 (frontal parietal cortex) electrodes of depressed patients and healthy controls. The figure below shows the frequency correlations of FP1/FP2 between depressed (blue) and control (red) for Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Theta waves. This was done to determine which waves had the largest differences between the two groups.

While the Alpha, Beta, and Theta waves seem to have considerable overlap, the Delta waves tell a different story: the control subjects seem to have lower frequencies of delta waves, while the depressed subjects seem to have higher frequencies. This is illustrated by the apparent skew of blue dots towards the upper right corner and the skew of red dots towards the bottom left corner in the Delta Wave figure.

This hypothesis is furthered by the results of running a Kernel Density Estimation on the same electrode data. As seen below, the frequency of Delta waves is skewed to the right when compared to the control, corroborating the evidence of the scatter plots.

This apparent difference immediately tells us that the delta waves are worth investigating further. Thus, we took our machine learning approach to build a predictive model that analyzes the delta waves in the FP1 and FP2 electrodes.

Unsupervised results

We started clustering analysis by first performing the algorithms on all measurements within the reduced dataset where each graph is the distortion against the number of clusters generated by the following algorithm:

def KMeans_analysis(K, data):

distortion = []

predictions = []

x_axis = np.arange(1,K+1)

for i in range(1,K+1):

km = KMeans(n_clusters=i)

km.fit(data)

distortion.append(km.inertia_)

predictions.append(km.predict(data))

return (x_axis, distortion, predictions)

Note: The graphs were all performed on PCA reduced datasets of varying variance, with the top graph being 85 percent, and the bottom being 95

It becomes evident quickly that the elbow plots generated by kmeans are very smooth, not seeming to level off at any particular point on the x axis, indicating that kmeans is having trouble clustering the data.

Its possible that the shape of the data is not circular but more eliptical, so we attempted to perform a GMM analysis instead. To measure the effectiveness of GMM, we calculated some external measurements, mainly fowlkes score and the normalized mutual information, and graphed the scores against the number of componenets per mixture mode.

Orange is kmeans, blue is gmm

The results of the GMM suggested that the soft clustering provided little similarity with the ground truth clustering (FMS) and that the predictions and true labels were virtually independent, never breaking past even .1.

The results of the first bout of unsupervised learning demonstrated that the dataset was incredibly noisy and needed further cleaning

As mentioned in the methods, subdata sets were generated, comparing each psychiatric disease against the healthy control for a total of 12 different subdata sets.

def disorder_vs_control_electrode(data, label, disorders, control):

newData = []

for value in disorders:

#print(value)

a = data.loc[data[label].isin([value, control])]

newData.append(a)

#print(newData)

return newData

Further analysis showed that these subdatasets leveled out at lower distortion, but were still too smooth to be considered good clustering. Too further reduce the noise of the dataset, we decided to try clustering by waves, seeing if that clustering around a particular frequency range would yield any meaningful results, what we got was much cleaner than previous attempts.

def develop_data(disorder_control, wave):

data = get_features(disorder_control, wave)

temp = disorder_control['specific.disorder']

data_labels = temp.replace(temp.unique(), [0, 1])

return data, data_labels

def create_byWave(data):

by_Wave = []

for wave in wave_types:

new_data, labels = develop_data(data, wave)

by_Wave.append((new_data, labels))

return by_Wave

A sample for 4 datsets is shown below:

Legend:

- blue -> delta

- green -> theta

- red -> alpha

- brown -> beta

- peru -> highbeta

- purple -> gamma

Interestingly, from the results it was revealed that clustering with only the frequency of alpha rhythm from cerebral sensors (Fp and F) minimized the distortion per cluster for a majority of diseases. That isn’t to suggest that strong alpha rhythm in the frontal cortecies are a good predictor of a particular disease, but rather a better indicator of abnormal electrical activity.

GMM was run with the same dataset and the following FMS plot was achieved:

def gmm_analysis(K, data, metric, arg):

distortion = []

for i in range(1,K+1):

gmm = GaussianMixture(i, max_iter=1000)

labels = gmm.fit_predict(data)

distortion.append(metric(arg, labels))

return distortion, labels

Scores peaking at .7 around 2 or 3 componenets was exactly what we were looking for. However it is also more likely that higher FMS values were achieved with lower number of componenets simply because fewer componenets meant that the number of true positives would not vary much. This is supported by the fact the graph starts highest on the first componenet and sharply decreases as more componenets are added, instead of starting low, and peaking at 2 componenets. It should also be noted that kmeans clustering performed similarly, further supporting that these results were not as meaningful. When scattering different features agaisnt each other, such as the prefrontal readings above, that the datapoints were all congealed around one central points, making labels hard to cluster.

Seeing how K_means and GMM performed, we tried hierarchial clustering and visualized the results

Hierarchial clustering seemed to be able to find disimilarities between clusters when provided only frontal sensor data, however when temporal, occipital and parietal sensor data was introduced we began to see more noise again, with the clusters on the dendograms merging at increasingly lower intervals.

Supervised results

The results of applying an SVM to the above dataset is shown below. We first used a linear kernel, but the results yielded a poor ~52% accuracy rate on the test data. This makes sense, given the abysmal boundaries of classification yielded by SVC w/ linear kernel and LinearSVC. Applying an RBF Kernel yielded even worse results, as the decision boundaries were nearly non-existent. However, when a polynomial kernel was used, the accuracy of the model increased by an enormous 15%, averaging at around 71% accuracy. The bottom right figure illustrates why this was the case; the decision boundaries are much more nuanced and capture the pattern of the control and depression data.

# Charting SVM

y = train_labels

h = .02 # step size in the mesh

# we create an instance of SVM and fit out data. We do not scale our

# data since we want to plot the support vectors

C = 1.0 # SVM regularization parameter

svc = svm.SVC(kernel='linear', C=C).fit(X, y)

rbf_svc = svm.SVC(kernel='rbf', gamma=0.7, C=C).fit(X, y)

poly_svc = svm.SVC(kernel='poly', degree=3, C=C).fit(X, y)

lin_svc = svm.LinearSVC(C=C).fit(X, y)

# create a mesh to plot in

x_min, x_max = X.iloc[:, 0].min() - 1, X.iloc[:, 0].max() + 1

y_min, y_max = X.iloc[:, 1].min() - 1, X.iloc[:, 1].max() + 1

xx, yy = np.meshgrid(np.arange(x_min, x_max, h),

np.arange(y_min, y_max, h))

# title for the plots

titles = ['SVC with linear kernel',

'LinearSVC (linear kernel)',

'SVC with RBF kernel',

'SVC with polynomial (degree 3) kernel']

for i, clf in enumerate((svc, lin_svc, rbf_svc, poly_svc)):

# Plot the decision boundary. For that, we will assign a color to each

# point in the mesh [x_min, x_max]x[y_min, y_max].

plt.subplot(2, 2, i + 1)

plt.subplots_adjust(wspace=0.4, hspace=0.4)

Z = clf.predict(np.c_[xx.ravel(), yy.ravel()])

# Put the result into a color plot

Z = Z.reshape(xx.shape)

plt.contourf(xx, yy, Z, cmap=plt.cm.coolwarm, alpha=0.8)

# Plot also the training points

plt.scatter(X.iloc[:, 0], X.iloc[:, 1], c=y, cmap=plt.cm.coolwarm)

plt.xlabel('FP1')

plt.ylabel('FP2')

plt.xlim(xx.min(), xx.max())

plt.ylim(yy.min(), yy.max())

plt.xticks(())

plt.yticks(())

plt.title(titles[i])

#plt.show()

#print(schiz_fullfrontal)

#print(control_fullfrontal)

# split data into training and testing

Other Supervised ML Algorithms used were:

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD): 71.4% Accuracy

Multilayer Neural Network (MPL): 58% Acucuracy

Decision Tree: 62% Accuracy

Discussion

Feature Selection/Engineering/Reduction

An important aspect of the study that needed investigation was the correlation of EEG signal between opposing electrodes. For example, we needed to verify that the FP1 electrode (right side front parietal) correlated with the FP2 eletrode (left side front parietal). This was verified by the red and blue scatter plot displayed in the Results section.

The specific features that were chosen were the frontal electrodes, as the frontal brain regions are the most important regions of interest when researching depressive disorders. Additionally, we decided to drop all coherence features due to the distortive impact it had on various learning algorithms, including clustering analysis and GMM.

Furthermore, for supervised learning, the Alpha, Theta, and Beta wave features were all dropped from the frontal electrodes. We decided to use this approach in order to maximize saliency of results: as seen in the scatter plots in the Results section, the delta waves had the least overlap for depression vs control in FP1 and FP2 electrodes. This illustrated that the delta waves were worth investigating further.

We used PCA for our dimensionality reduction because we already had to standardize our features beforehand for other reasons. Thus, it made the most sense to implement PCA, since the dataset was already normalized/standardized. Additionally, we used PCA is order to remove correlated features, such as overlapping waveforms. Moreover, the ease-of-use of PCA along with the ease of visualising the results made the algorithm a particularly attractive option for dimensionality reduction.

Unsupervised Learning methods

The target variables were a series of digits, ranging from 0 to 11, mapping to the actual disorders in the original set. There were no noticable imbalances within the dataset that would make one target preferred over the other.

Choice of metrics

For our clustering algorithms performance we chose to use sum of square distances to measure the performance of Kmeans, as well as Fowlkes and normalized mutual information for our GMM.

Sum of square distances was appropiate for K means as it is an apt measurement for visualizing the level of distortion across clusters. The distances will be very high when points are generally far away from their cluster and low when they are very close, giving a certain sense of ‘compactness’ to the data.

Fowlkes-mallow score measures how ‘similar’ two sets of clustering are based on their labels. More mathematically, it is the geometric mean of the pairwise precision and recall. This measurement tells us the degree to which our clustering keeps ‘true positives’, or rather correct classifications of the condition. This is useful as we are making a psychiatric classifier and wish to priortise our precision and recall rather than our accuracy.

Normalized mutual information measures how much the predicted assignments and true assignments ‘agree’ with each other. This value is 1 when there is perfect agreement and 0 when there is no agreement, or in other words the assignment and ground truth are seemingly independent. This gives us a certain correlational sense of whether or not our model is accurately predicting data points or not.

Clustering analysis

When discussing the clustering results, it is important to understand the nature of our measurements.

EEG data is measured by electrodes placed atop the scalp. However, the non-invasive nature of the procedure severely reduces its spatial resolution. In laymens terms, EEG sensors cannot grasp electrical activity of deeper subcortical networks, and can only really read data from superficial neural activity. Understanding this is key to feature selection because it suggests that certain electrodes such as T and C, meant to read data from temporal and central neural structures, may not be as refined, as they are reading information from structures more dorsal than ventral.

This can prove to be problematic due to the systemic nature of most psychiatric disorders. Schizophrenia for example, has strong visual biomarkers within the prefrontal and temporal neural structures. Having good access to only one of structure’s electrical activity, can possibly leave out much needed information for classification.

When comparing the effectiveness of GMM and kmeans we see that they actually performed quite similarly.

Kmeans only considers the average of the clusters while clustering while GMM also considers the variance, this is what causes the elliptical and circular shapes that they capture in data. This means that the variance of our data seemingly has little impact on the performance of GMM. This is further supported by the NMI scores, showing that GMM and Kmeans predictions could hardly be agreed with by the ground truth analysis.

Generally speaking across our data, its very difficult for classification to cluster well. Only after breaking apart the datasets many times across different layers can we get the algorithms to have some form of decent distortion drop off. This could be due to many factors, such as the loss of information when transitioning from time series to frequency, or the lack of spatial resolution in EEG data. Clustering algorithms generally perform poorly when there is no real model to capture in the data, suggesting that the dataset collected doesn’t accurately capture the specified target variable under the current conditions.

Supervised Learning Methods

In the medical field, Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are a popular method of supervised machine learning. This is due to the fact SVMs specialize in binary classification, resulting in a robust medical tool to use for predictive diagnosis.

The scoring of our models was the amount of labels it marked correctly over the whole, otherwise known as its accuracy. This allows us to measure how well our models might perform with new data.

The poor results given by the MLP are likely due to the lack of training data – there were only around 400 training points for the network to learn from. If more training data (several thousands) was present, the network would likely have performed better. The decision tree did not perform well due to the number of features in the dataset, as the algorithm usually breaks down once a large number of features is reached.

Interestingly, the SGD algorithm, on average, performed the best out of all algorithms. This is likely due to the nature of SGD, and how it is less likely to get stuck in local minima of the loss function (shown below).

(from https://towardsdatascience.com/why-visualize-gradient-descent-optimization-algorithms-a393806eee2)

This is due to the fact that SGD is online and updates frequently, relative to other learning algorithms. For this reason, the SGD performs particularly well on large datasets such as the EEG dataset used in this study.

Overall, the classification models all attempted to learn the model of our data, but only SGD and SVM provided the best results. This is likely due to the fact that the other models used, neural nets and decision trees, are highly susceptible to overfitting, especially for smaller datasets.

Conclusion

In this project, we looked at EEG data of psychiatric patients and healthy patients. We started by narrowing our scope to specifically patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), and then ran algorithms to reduce the dimensionality. Afterwards, we ran both unsupervised and supervised learning algorithms on the frontal lobe data of healthy patients and MDD patients. We found that after targeted dimensionality reduction, K-means clustering offered a relatively effective model, as seen from the elbow plots. Additionally, using a Support Vector Machine with a polynomial kernel yielded a model with an impressive 70% accuracy in binary classification (MDD vs no MDD). Further, stochastic gradient descent yielded a 72% accuracy. This project can be labelled a success, as we trained multiple models that gave acceptable accuracies (>70%). However, further research and experimentation is needed, as 70% accuracy is still too low to be used an a clinical setting.